Every Sunday for the last 12 years, Vietnam War veteran Robert Rosebrock has stood on the corner of Wilshire and San Vicente boulevards in West Los Angeles, protesting the alleged misuse of the property behind him.

The 388-acre parcel of land houses the Veteran Affairs (VA) Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, including a VA hospital. It’s on a huge chunk of prime real estate—about three-quarters the size of Disneyland—in the heart of L.A.

It is also home to a number of third-party lease agreements. Those include a UCLA baseball field, a private school campus, a theater, and a dog park.

Rosebrock, 78, says these agreements violate the mandate of the land—to serve veterans’ health. And he holds his weekly protest to demand the land be returned to that purpose. June 7 marked his 637th consecutive Sunday protest.

“I get up every morning knowing that today could be my last day, so I just keep going,” Rosebrock told The Epoch Times. “There’s no time to rest.”

Rosebrock’s inaugural protest was on March 9, 2008. The VA had entered an agreement with the nonprofit Veterans Park Conservancy to allow a public park on the land, rent-free. Rosebrock wanted to see new housing built for disabled and homeless veterans instead.

Now, his urgency is greater amid the COVID-19 pandemic. He has seen an increasing number of homeless veterans sleeping on the sidewalk outside the land’s perimeter fence.

The Weekly Protests

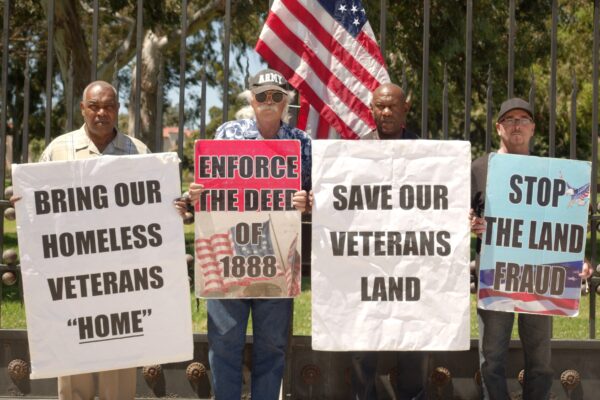

That first protest in 2008 drew about 100 participants. The number of protesters who have joined him since varies; three were with him on June 7.

Often he is joined by veterans who served in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam—part of what he calls the “Old Veterans Guard.” Other times, he stands alone.

“There’s so many times I’m usually the only guy out there,” he said. “I wear it as a badge of honor.”

He holds a sign, “Enforce the Deed of 1888.” It refers to the Land Grant Deed of 1888, which required states set aside land for the care of veterans. The parcel of land in L.A. was donated under the purview of that Deed by prominent socialite Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker (d. 1912).

In the 1970s, the VA began leasing some of the land to non-veteran, commercial entities.

Rosebrock says those entities continue to thrive, while the veterans’ facilities have deteriorated. For the past decade, the appropriate use of the land has been debated in court and by lawmakers.

A Decade of Debate

In 2011, four homeless veterans, along with Vietnam Veterans of America, filed a lawsuit alleging misuse of the property. The suit stated that 30 percent of the land was not being used in the service of veterans.

In 2013, a federal judgment agreed with the plaintiffs, and deemed that nine real estate deals on the campus were “unauthorized by law and therefore void.” Brentwood Schools, UC (University of California) Regents, and Twentieth Century Fox Television were among the entities listed.

In 2015, the suit was settled when VA Secretary Robert McDonald and the attorneys for the plaintiffs, including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), agreed to develop a plan for the site together that would better serve homeless veterans.

In January 2016, the VA released its Draft Master Plan, designed to “determine and implement the most effective use of the campus for Veterans, particularly for homeless Veterans.”

“We call it the ‘Draft Master Scam,’” Rosebrock said.

“They have done zero towards this, and the earliest it will be accomplished, if ever, is a decade away.”

In September 2016, Congress passed The West Los Angeles Leasing Act of 2016, which permitted third-party leases, provided they primarily benefit veterans and their families. The revenue from the leases must also be used for renovation and maintenance of the veteran medical facilities.

“It’s like renting out the front lawn of the White House to pay for Secret Service police, or leasing out our military bases to generate revenue for national defense,” Rosebrock said. He thinks the use of land for veterans should be more direct.

Some of the campus tenants have established services for veterans, including UCLA, which has its baseball team’s stadium on the campus. In 2017, it opened a legal clinic and family wellness center to support veterans as part of its 10-year, $16.5 million lease agreement.

A 2018 report by the VA Office of the Inspector General concluded, however, that 25 out of 40 land use agreements on the campus were “improper.”

That included a 12-acre city park, Veterans’ Barrington Park. It was intended to principally benefit veterans and their families, but the report found no evidence of veteran focus.

Several longtime occupants, including UC Regents and Brentwood School, remain on VA property with new leases.

UC Regents and Brentwood School did not respond to requests for comment; nor did the city parks department and the VA.

“There’s no doubt in my mind. We have won a lot of battles, we haven’t won the war,” Rosebrock said. “We’re still the capital for homeless veterans.”

‘Skid Row’ to ‘Veterans’ Pride Row’

California has more homeless veterans than any other state. About 11,000 veterans are homeless in the state of California, according to a 2019 report from the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. That’s nearly four times the amount in Florida, which has the second highest number of homeless veterans.

L.A. County has the most homeless veterans in California—about 3,500, according to a 2019 estimate by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

“There’s an old saying: We honor our dead veterans by taking care of our living veterans,” Rosebrock said. He has made every effort “to bring attention to the public eye that our homeless veterans are in danger.”

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the VA has opened new bridge facilities with hundreds of additional beds to support needy veterans. It has also provided showers, restrooms, and meals for homeless veterans, who are allowed to camp on the premises.

Rosebrock has been part of an effort to purchase and set up 14-by-10-foot walk-in tents and cots for the disabled and homeless veterans sleeping on the sidewalk outside the land’s perimeter fence.

He hopes to transform “Brentwood Skid Row” into “Veterans’ Pride Row,” he said.

He has helped set up 25 tents outside the campus. On the other side of the fence, a number of smaller tents have been set up on a VA parking lot, he said.

“I’ve always tried to operate under the golden rule,” Rosebrock said. “If I was homeless, what kind of a person would I want working for me? I try to be that.”

His efforts over the years have earned him six arrests. The most recent was on Memorial Day 2016.

He displayed American flags on the perimeter fence. The act qualified as a federal misdemeanor—it was unauthorized posting of materials or “placards” on VA property. He was acquitted.

“They were trying to send a message to stop what I’m doing,” he said. “It only made me stronger.”